In the midst of the extreme summer heat of 2025, water shortages have pushed Ukraine’s Russian-occupied Donetsk Region to the brink of humanitarian disaster. Pro-Russian media blame Ukraine for the crisis, but the region’s water system has been steadily deteriorating since Russian troops crossed Ukraine’s borders back in 2014 — and it has suffered even more since the start of the full-scale invasion in February 2022. Officials who for years ignored the problem now find themselves powerless in the face of the ongoing drought.

Water supply has historically been a major issue for Donbas. Much of the region lies in dry steppe, with no large rivers or lakes, and the rapid population growth that occurred after Soviet industrialization efforts demanded immediate solutions.

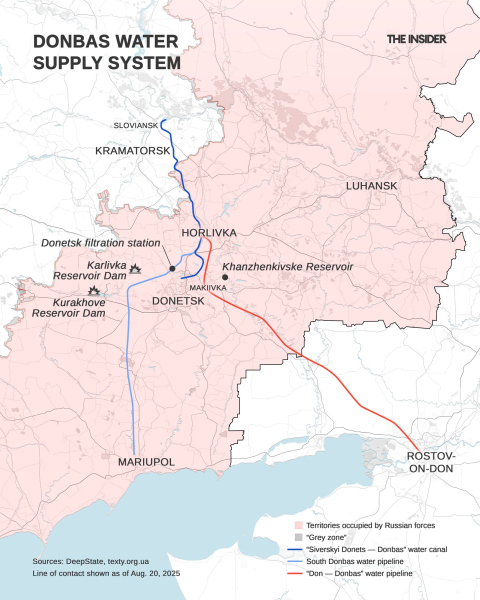

In 1958, the 133-kilometer “Siverskyi Donets–Donbas” canal was built to connect the Siverskyi Donets and Kalmius rivers. The canal became the main source of water for the Donetsk region, providing 94% of its needs. A network of reservoirs was also created for emergencies, and another key artery was the South Donbas pipeline, which carried water south to Mariupol.

Even before 2014, however, the system was vulnerable, requiring expensive maintenance due to industrial strain, pollution, and resource depletion. Corruption made matters worse: in 2013 the local outlet Donetskaya Pravda, backed by the Vidrodzhennia foundation, exposed a scheme involving shell companies tied to Donetsk officials and the leadership of the regional utility Voda Donbassa (lit. “Water of Donbas”).

A similar situation unfolded in the Luhansk region. Under the rule of the pro-Russian Party of Regions, the entire water system ended up controlled by a shell firm with unclear beneficiaries registered in the British Virgin Islands. Still, those corruption scandals involving regional elites were soon overshadowed by the devastation that hit the Donbas once Russia launched its “hybrid war.”

Read more about how the Donetsk Region’s residents are coping with the water crisis in The Insider’s special report.

Despite its critical role in keeping the region alive, the water infrastructure of the Donbas repeatedly came under fire during the regional conflict of 2014-2022. Pumping and filtration stations supporting the Siverskyi Donets-Donbas canal were shelled by Russian-backed separatists, and employees of Voda Donbassa had to repair them at risk to their lives.

By 2021, nine employees had been killed and 26 injured. UNICEF documented more than 450 cases of damage to water facilities in the Donetsk Region from 2016 onward — not counting the worst incidents, which occurred in the first two years of war.

Until February 2022, the Siverskyi Donets-Donbas canal continued supplying water to parts of the Donetsk Region controlled by the so-called “Donetsk People’s Republic,” or “DPR,” a breakaway Russia-backed entity annexed by Moscow in 2022. The Donetsk filtration station remained a neutral facility, accessible only to OSCE representatives and the Ukraine-Russia Joint Center for Control and Coordination, created under the 2015 Minsk agreements. Both the canal and the filtration plant were listed in the Minsk protocol as strategic lifeline facilities that were to be placed in a demilitarized zone. Even so, they were periodically shelled.

Voda Donbassa operated under Ukrainian law, though half of its employees and two-thirds of its customers lived in separatist-held areas. The leadership of the “DPR” exploited this reality by setting “subsidized” utility tariffs that were half the price of those in areas controlled by Ukraine (where rates were already among the lowest in the country). Payments were made by “barter” — electricity and chlorine from captured Ukrainian power plants and chemical factories in exchange for water.

This led to chronic underfunding for maintenance. By 2020, Voda Donbassa had become Ukraine’s largest debtor, owing about 5 billion hryvnias (€150 million) for electricity. Of that, 3.9 billion came from consumers in territories not controlled by Kyiv.

The leadership of the “DPR” exploited the situation by setting “subsidized” utility tariffs that were half the price of those in areas controlled by Ukraine.

In 2021, the Ukrainian Donetsk regional administration raised the issue of modernizing Voda Donbassa’s networks, including the part that ran through DPR-held territory (a project that could also benefit Kyiv’s reintegration strategy). President Volodymyr Zelensky backed the idea and promised to find the 30 billion hryvnias needed. But when the conflict escalated into a full-scale war, replacing the pipes became impossible.

After Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, the Donbas water canal infrastructure became a frontline target. As Sophie Lambroschini, an expert on Ukraine’s wartime economy at the Marc Bloch Center in Berlin, noted:

“The water situation in the Donbas region has been complicated by war since 2014. The region has few resources given the intense consumption of the water-hungry metals and coking industries and the densely populated areas. With few exceptions, the water stems from a small river, the Siverskyi Donets, flowing in the north.”

Not only pumping and filtration stations came under attack but also siphons, locally known as “duikers” — massive overground pipe bridges with additional pumping equipment that allowed the canal to cross ravines and rail lines. In one example that took place near Chasiv Yar, Russian troops destroyed water pipes that were blocking the passage of armored vehicles. The canal was also damaged when Ukrainian forces struck Russian troops who were using the same pipes as cover.

Reservoirs across the Donbas were also hit. In 2023, fighting around Avdiivka destroyed the Karlivka reservoir dam, threatening nearby villages with flooding. In 2024, Russian forces blew up the Kurakhove reservoir dam, which supplied cooling water to a local power station, which they also destroyed.

The crisis was compounded by the destruction of the Oskil reservoir dam in the Kharkiv Region. Russian forces demolished it during their retreat in September 2022. The reservoir had been essential to maintaining water levels in the Siverskyi Donets-Donbas canal. Ukraine’s Security Service filed charges in absentia against Russian generals Oleg Tsokov and Oleg Makovetsky, who allegedly ordered the demolition.

These actions drained fresh water reserves and disrupted the region’s ecological balance. “For decades, sediments containing heavy metals, fertilizer residues, organics, and petroleum products accumulated at the bottom of artificial reservoirs. When the dam breaks, these toxins don’t just sit on the surface — they spread into the environment. That means poisoning not only water but also soil, air, and food chains. The risk of cancer rises, farming becomes impossible, and sometimes even life itself is unsustainable there,” said Ukrainian environmentalist Oleksandra Rozanova.

Occupation authorities in the self-proclaimed “DPR” shifted blame for the water crisis onto Ukraine, with pro-Kremlin media talking of a “water blockade” against the region. In reality, no credible evidence was presented indicating that Ukraine had cut off the Siverskyi Donets-Donbas canal. Instead, its main supply channel was simply destroyed due to the Russian invasion.

However, the water shortages became another instrument used by the Kremlin to justify its stated aim of fully capturing the Donetsk region — which would allow Russia to seize control of what remained of the canal. “Full restoration work is only possible when the entire length of the canal, including underground sections, is under firm Russian military control,” wrote pro-Kremlin newspaper Vzglyad.

As an alternative, occupation authorities relied on a water pipeline from Russia’s Rostov region built at the end of 2022. Pro-Russian press hailed the infrastructure project as a triumph: “The pipeline was built in record time. The decision was made in November 2022, construction began in December, and within just four months it was completed.”

But the new canal failed to solve Donbas’s water problem. Its capacity was too low and breakdowns were frequent. “DPR” officials admitted it met only 45% of the region’s needs. Later, Russian ultranationalist circles blamed the project’s failure on former Deputy Defense Minister Timur Ivanov, who was convicted of corruption in 2025. His case did in fact include the taking of bribes from Olimpcitystroy, a company involved in the project.

The current water crisis erupted this summer after the degraded infrastructure was further strained by heat and drought. Surviving reservoirs in the Donetsk Region dried up. Cracked mud flats appeared in place of the Khanzhenkivske reservoir near Makiivka. In Donetsk, water was supplied only once every three days; in Yenakiieve, the hometown of ex-President Viktor Yanukovych, once every four.

The shortage reached such proportions that even “Novorossiya patriots” admitted its scale. Former Ukrainian MP-turned-separatist Oleg Tsaryov took to Telegram to describe the grim realities in Donetsk:

“In Donetsk, water comes once every three days. You can’t flush toilets. It’s normal here: people put a plastic bag in the toilet. The decent ones throw the bags in the trash. The rest dump them out their windows.”

Experts say Donbas has suffered droughts before, but today’s catastrophic crisis is not the result of natural phenomena, but of war coupled with administrative incompetence. “Natural conditions may be tough, but with resources and expertise the problem could have been solved. For Russia, these territories are trophies. Nobody will care about the people. Barbarism, lack of governance, lack of coordination — that’s the source of the crisis,” said Ukrainian environmentalist Vladyslav Antipov.

Ukraine’s fugitive ex-PM Mykola Azarov, now in Russia, implausibly blamed Ukraine for the drought: “Now Donbas has its usual dry weather with high heat. People are suffering from a humanitarian catastrophe, which, by the way, was orchestrated by Kyiv under orders from its Western masters.”

The situation has been aggravated by the incompetence of occupation officials, many of them Russian “parachuted managers” working on rotation, with little knowledge of the region or interest in understanding it. In 2022-23, the so-called DPR’s construction and housing ministry was run by Eduard Osipov, a former deputy chief of the Russian federal agency Centravtomagistral, which oversees the road network around Moscow. His number two was Andrei Nagaitsev, a former FSB officer and ex–deputy mayor of Biysk.

In 2023-2024, the post went to the ex-head of St. Petersburg’s construction inspectorate, Nikolai Tsiganov. He was succeeded by Donbas native Vladimir Dubovka, who had worked in housing services before 2014 but carried a dubious reputation: local bloggers claim he was linked to the crime boss Nesterov, the so-called “overseer” of Amvrosiivka. In 2014, Dubovka reportedly wore a T-shirt of the Ukrainian ultranationalist group Right Sector and voiced pro-Ukrainian views, but he later switched to the “DPR” in order to further his career. The region’s Ministry of Emergency Situations is run by Alexei Kostrubitsky, who is best known for his role in drunken public behavior.

The crisis may topple Denis Pushilin, who has led the “DPR” since 2018, when his predecessor was assassinated by a bomb placed at the “Separ” cafe in Donetsk. Pushilin was confirmed as head of the annexed region in 2022, but rumors of his possible dismissal have circulated for months.

Meanwhile, Pushilin is trying to frame the crisis as another chance for Russia to “save Donbas” from the problems that Russia itself created. He appealed to Putin and secured a personal audience. At the meeting, Pushilin admitted that “network wear and tear” had caused losses from the system of up to 60% in some places, though he reported that convoys of trucks were on their way to deliver water to Donetsk.

After the meeting, Mariupol journalist Mykola Osychenko calculated that the promised deliveries would amount to a mere 600 grams of water per person in the Donetsk metropolitan area, and Pushilin stressed that the priority for the “authorities” remains a military solution: “We will only have water once Sloviansk is liberated and the Siverskyi Donets-Donbas canal is restored.”

Pushilin also has a personal stake in the situation. On Aug. 4, at the peak of the crisis, he personally drove a water truck to deliver supplies. Notably, rumors suggest Pushilin owns bottling plants from which his administration buys water at inflated prices using public funds.

Ultranationalist Telegram channels hostile to Pushilin predict his downfall, but so far there is no sign the Kremlin has withdrawn its support. As Ukrainian journalist Denys Kazansky, who represented Ukraine in the Trilateral Contact Group on Donbas from 2020 to 2022, told The Insider:

“I always thought Pushilin was kept around so they could one day blame him for everything and sack him, but for now he’s still around. Apparently Putin doesn’t care about Donbas water problems. Or maybe he’s told it’s all under control. We don’t know what world he lives in or where he gets his information.”

Another version of events, voiced anonymously by a Russian political consultant who worked in Donbas, asserts that Putin dislikes making decisions under pressure and may remove Pushilin later under a different pretext. Much depends on how effectively Pushilin sells the narrative of Donbas being “saved” by Moscow.

In any case, the problem persists: Donetsk is still suffering from water shortages, and bleak scenarios are being discussed, including the forced evacuation of “excess population.” As Ukrainian journalist Dmytro Durnev recalled: “Donetsk already went through such an evacuation in 2022, when occupation authorities declared a coming ‘Ukrainian offensive.’ The next day, mobilization began, and then the big war. Time has shown that after 11 years of occupation, anything can be done to the people left behind.”

Russia’s aggression in the Donbas, which began in 2014, has led not only to the region’s dehydration, but also its depopulation — a process Putin once claimed he was aiming to prevent under the banner of fighting “genocide.”