In late June 2023, Russia witnessed its first armed rebellion of the 21st century. Wagner Group forces under the command of Yevgeny Prigozhin advanced steadily toward Moscow, only to abruptly turn back just a few hundred kilometers from the capital. A remarkably similar episode took place in the summer of 1918, when Left Socialist-Revolutionaries outraged by the signing of a peace treaty with Germany launched an armed uprising that came close to toppling Bolshevik rule — stopping just a few hundred meters from the Kremlin, which at the time was defended only by a small garrison of Latvian riflemen. Yet the Left SRs lacked a leader capable of orchestrating a decisive operation, and the Bolsheviks ultimately defeated the poorly coordinated rebel forces.

The first Soviet government was a two-party coalition. Alongside the Bolsheviks, it included the Party of Left Socialist-Revolutionaries (Left SRs), who represented the radical wing of the forces that came to power following the October Revolution of 1917. The Left SRs were granted eight People's Commissariat posts and significant representation across other Soviet institutions. Notably, the second-in-command of the Cheka after Felix Dzerzhinsky was Left SR member Vyacheslav Aleksandrovich. As Deputy Chairman, he had the authority to sign documents and issue orders on Dzerzhinsky’s behalf.

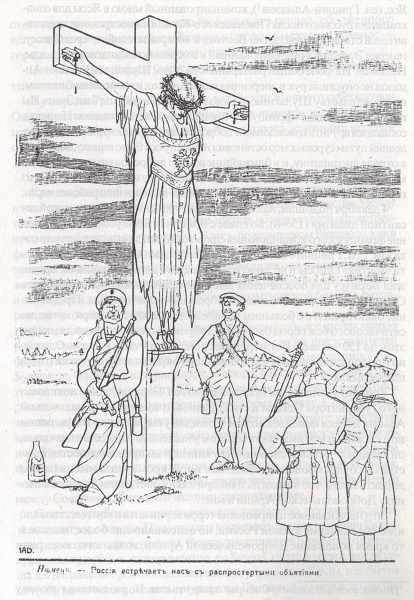

But the «honeymoon» between the Bolsheviks and the Left SRs was short-lived. In March 1918, the Left SR Commissars voted against the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which ceded Russia’s control over Ukraine, Belarus, Poland, and the Baltic States in exchange for peace on World War I’s Eastern Front. In protest, the party announced its withdrawal from the government, but it did not surrender its positions in the new state’s structures of power — most notably within the Cheka. The Left SRs had no intention of severing ties entirely and pledged to «support the Bolsheviks as honest fighters on all fronts except the issue of peace.»

However, as the Bolsheviks’ domestic policies grew increasingly repressive, the Left SRs became more vocal in their criticism of what they called «commissar rule,» urging an immediate correction of the Soviet political course. Their idea of a «correction» was to resume the war with Germany, and on June 24, the Central Committee of the Left SRs drafted a plan: at the upcoming Fifth Congress of Soviets, they would demand that the Bolsheviks annul the humiliating treaty. If the demand was refused, they would carry out a series of terrorist attacks targeting German representatives in an effort to undermine the fragile Moscow–Berlin relationship.

“What we need is not an uprising, but a real war and an Anglo-French orientation, which is more beneficial not just to a certain political party, but to the country as a whole,” said Central Committee member Ilya Mayorov. “It is in our interest to ensure that Germany suffers defeat at the front. That would spark a revolution there — one that could save us.”

The Fifth Congress of Soviets opened on July 4, 1918, at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow, where the Left SR delegates demanded a complete break with Germany and a declaration of war. The official transcript of the Congress reads: “What we have is not an independent Soviet government, but lackeys of German imperialism. (Uproar.) Yes, lackeys of German imperialism.” However, it soon became clear that these demands were destined to fall flat. Manipulation of proportional representation from various local Soviets had given the Bolsheviks a decisive majority — 773 delegates versus 353 supporting the Left SRs. Thus, the second part of the plan had to be set in motion.

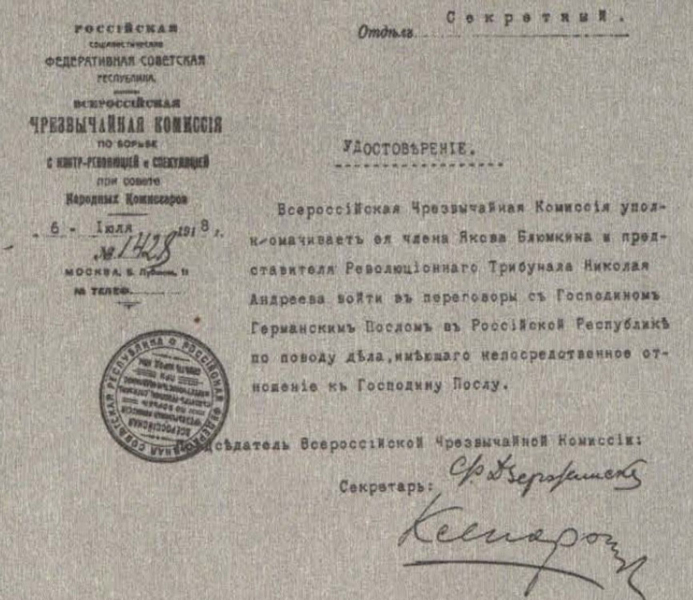

The Central Committee of the Party of Left Socialist-Revolutionaries-Internationalist selected as their primary target Count Wilhelm von Mirbach, the German ambassador to Moscow, as the party leadership reasoned that his assassination would spark a furious reaction from Berlin. The man assigned to carry out the operation was Yakov Blumkin, a Left SR and head of the Cheka’s counterintelligence division. On the morning of July 6, he received from Vyacheslav Aleksandrovich official seals for forged documents, as well as a car. Blumkin and his accomplice, Nikolai Andreyev, arrived at the German embassy under the pretense of needing to discuss an urgent matter. Once face-to-face with Mirbach, they opened fire.

The ambassador died on the spot. However, during their escape, the attackers accidentally left behind a briefcase containing documents. When Felix Dzerzhinsky arrived at the embassy shortly afterward, it did not take him long to identify the perpetrators and deduce where they might be hiding. He immediately proceeded to No. 1 Bolshoy Trekhsvyatitelsky Lane, where the Cheka's Combat Detachment — commanded by Left SR Dmitry Popov — was stationed. Dzerzhinsky demanded that the terrorists be handed over. Instead, Dzerzhinsky himself was taken hostage. The Bolsheviks responded by arresting the entire Left SR faction at the Fifth Congress — right inside the Bolshoi Theater.

The Left SRs took Dzerzhinsky hostage

The Left SRs’ next move was to seize control of the telegraph office, central post office, and telephone exchange, sending communications all across Russia proclaiming that “the Russian people have been freed from Mirbach.” Then came a long pause.

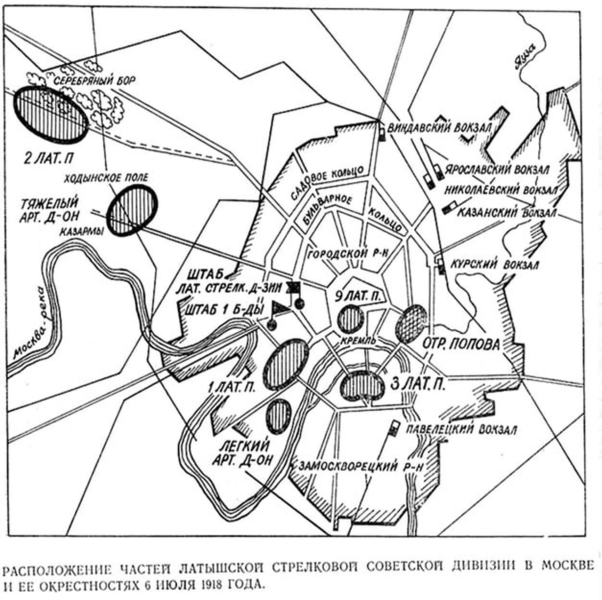

The Left SRs’ main force consisted of Popov’s detachment — 1,000 infantry supported by an artillery battery and four armored cars. This may have seemed insignificant in comparison to Moscow’s 20,000-strong garrison, but in reality, most of those units declared their “neutrality.” The situation closely mirrored that of Petrograd in November 1917: according to historian Richard Pipes, only 4% of the Petrograd garrison could be considered pro-Bolshevik at the time, and yet that small number had been enough to carry out a successful coup — mainly because the Provisional Government had no loyal troops at all.

The distance between Red Square and the headquarters of the Combat Detachment — where, by the evening of July 6, most members of the Left SR Central Committee had gathered — is right around one kilometer. In his memoirs, Joachim Vatsetis, commander of the Latvian Rifle Division guarding the seat of power, openly admitted that had Popov attacked the Kremlin, “the Bolsheviks likely would have been unable to hold it… and by the next day, Russia would have had a new government.” From a purely technical standpoint, the operation was entirely feasible: the Kremlin gates could have been destroyed by direct artillery fire, allowing the rebels to break through in their armored cars.

As Kremlin commandant Pavel Malkov later recalled, immediately after the Left SR uprising began, the Kremlin garrison — 925 riflemen from the 9th Latvian Regiment — was placed on high alert. Platoon-level posts were set up at the gates, three machine-gun companies were deployed along the Kremlin walls, and two companies were held in reserve. In reality, however, the 9th Regiment had little real combat capability. On July 6, after lengthy disputes with Bolshevik commissars, two Latvian companies reluctantly agreed to recapture the Central Telegraph from the rebels. Their «attack,» however, ended in a bloodless surrender to the Left SRs — the riflemen were disarmed, then given permission to return to the Kremlin.

The other Latvian units stationed around the city showed a similar lack of enthusiasm. Joachim Vatsetis later recalled that on the evening of July 6, the division’s chief of staff, former Imperial Army colonel Kosmatov, approached him and resigned on the spot: “You know what you're dying for. But what am I dying for? The entire garrison is against the Bolsheviks. And you think a handful of your Latvians can win this?”

Latvian units showed little willingness to defend the Bolsheviks

At first, Lenin hesitated to involve the Latvian units in suppressing the uprising. As prominent Bolshevik Karl Danishevsky later recalled, “unsettling rumors were circulating about certain commanders of the Latvian regiments.” Even Vatsetis himself was not fully trusted inside the Kremlin. He was asked to prepare an operational plan, but he was warned that someone else would be put in charge of carrying it out.

The situation changed only when it became clear that there was no “someone else” — and no other troops willing to fight against the Left SRs. The commissars of the Latvian Division personally vouched for Vatsetis, and Lenin summoned him to his office and anxiously asked: “Comrade, can we hold out until morning?” Even after receiving a confident “yes,” Lenin ordered two additional commissars to be assigned to Vatsetis's staff. The following day, Lenin would check in every two hours to confirm that Vatsetis hadn’t defected to the Left SRs.

Contrary to the portrayal in Soviet historiography, which consistently depicted the Latvian Riflemen as “unyielding Leninists,” the Bolshevik leadership in 1918 had every reason to question their loyalty. For the most part, the Latvian Riflemen viewed their alliance with the Bolsheviks purely in terms of self-interest, and Vatsetis was no exception. Immediately after the end of the Civil War, more than half of the Latvian Division’s Riflemen returned to their ”bourgeois” homeland, uninspired by the prospect of building socialism in the world’s first “state of workers and peasants.”

The Latvians’ rationale was simple: in 1917, Lenin had offered them everything they could imagine — peace, independence, and land they had long dreamed of seizing from German barons. But by the summer of 1918, that magnificent trio had entirely vanished. The riflemen had gone straight from the trenches of World War I into the chaos of the Russian Civil War, and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk had handed Latvia over to German control. The Left SRs rose up under the very slogan of overturning the “shameful Brest-Litovsk treaty,” and the Bolsheviks had every reason to believe the Latvians would find that idea appealing.

Why, then, didn’t Vatsetis side with the Left SRs? First, after witnessing the Russian command firsthand during World War I, he wrote in his memoirs: “A culturally backward country like Russia…could somehow manage to win over Turkey or smaller Asian nations, but the Russian people were incapable of waging war against the civilized nations of Europe.” Second, after finally knocking Russia out of the war, Germany launched a major offensive in France in March 1918 and — for the first time since 1914 — achieved a breakthrough on the Western Front. By July, the Kaiser’s forces stood just 60 kilometers from Paris and were preparing for a final push.

Under such conditions, the idea of Russia reentering the war — now against a victorious Germany — seemed like pure suicide to Vatsetis. And so he chose a different path. In the spring of 1918, he established contact with staff at the German embassy in Moscow, and in exchange for guarantees that he and his riflemen could return safely to Latvia, he was prepared to place his division fully at Germany’s disposal — even if that meant helping to overthrow the Bolsheviks.

But Berlin had no interest in toppling the Bolsheviks, as they were the only political force in Russia capable of upholding the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Instead, on July 6, Vatsetis received a very different message from the Germans — one that, according to embassy first secretary Kurt Riezler, was accompanied by a substantial payment in gold that was intended to motivate the wavering Latvian riflemen to act against the rebellious Left SRs

The Bolsheviks were the only Russian political force capable of upholding the Brest-Litovsk Treaty

Lenin was clearly aware of Vatsetis’s backchannel contacts with the Germans, which helps explain his deep mistrust — which lingered on even after the Left SR uprising had been successfully suppressed.

The End of the Uprising

By the morning of July 7, Vatsetis had managed to gather around 3,000 troops to the Bolshevik cause, but the quality of these forces was still poor. They spent seven hours in a fruitless firefight with Left SR commander Popov’s detachment, which had entrenched itself in Trekhsvyatitelsky Lane — and failed to advance a single step. “What diggers! Good thing our enemy was docile — he rose up, claimed victory, and went to sleep. Otherwise, with an army like this, we’d have been in real trouble,” Danishevsky’s memoirs record Lenin as having said about the fighting that day.

However, as in the suppression of past Russian revolts, it was the regime’s heavier weaponry that proved decisive. Eduard Berzin — commander of the Latvian Division’s artillery battalion and a future architect of the Gulag system — managed to position one gun with a direct line of fire on Popov’s headquarters. The very first shell exploded near the room where the Left SR leadership was meeting. They immediately fled, and by the seventeenth shot, the rest of the rebels were in full retreat too.

Popov’s fighters fell back toward Kursky Station, intending to seize a train. But the plan failed. Abandoning two artillery pieces and an armored car near the station, around 300 rebels fled Moscow via the Vladimir Highway. They were later surrounded in the Moscow suburbs and surrendered. By 2:00 p.m. on July 7, the last pockets of resistance had been crushed, and the hostages — including Dzerzhinsky — were freed.

“What tremendous historical significance those 17 shells had!” exclaimed Vatsetis in his memoirs. Indeed, few times in history has an uprising with the potential to alter the fate of a vast country been suppressed with such minimal effort.

In May 1918, two months after the signing of Brest-Litovsk and two months before the Left SR revolt in Moscow, Bolshevik authority had collapsed across the vast expanse from the Volga to Vladivostok following the Revolt of the Czechoslovak Legion. In Samara, a Right SR-led government was established, rallying under the slogan of war against the “German-Bolsheviks” and vowing to “expel German troops from Russia and bring the war to an honorable peace.”

On July 10, the commander of the Red Eastern Front — Left SR Mikhail Muravyov — rebelled, refusing to obey the Soviet government and sending a radiogram to Samara proposing a joint war against both the Germans and the Bolsheviks. Had the Central Committee of the Party of Left Socialist-Revolutionaries (PLSR) been sitting in the Kremlin at that moment, there would have been no need for rebellion — the shift of power would have occurred naturally.

What could Germany have done in response? Unlike in February 1918 — very little. Most of its troops had already been redeployed from Russia to the Western Front, where on July 18 the Allies launched their first successful counteroffensive that forced the Kaiser’s army into full-scale retreat. The collapse of Germany was just four months away.

Resuming the war against Germany not only would have reconciled the Reds and the Whites, but also secured Russia’s place in global politics as one of the victorious powers. This, in turn, would have meant a completely different balance of power within the post-Versailles order.

As for the domestic situation, despite their revolutionary zeal, the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries were staunch opponents of the death penalty and relied heavily on the middle peasantry (and, by the spring of 1918, even on the wealthier kulaks). They could have presented a much more moderate alternative to the Bolshevik experiment.

All that separated Russia from that alternative was one kilometer — the distance from Treshchsvyatitelsky Lane to the Kremlin. A distance the SRs ultimately failed to cross.

As the failed uprising, the leader of the Left Socialist-Revolutionary Party, Maria Spiridonova, insisted that they had not aimed to seize power, but merely to carry out “an act of international terrorism — a protest to the entire world against the suffocation of our revolution.” All subsequent actions, she argued, were acts of self-defense against “the Bolsheviks, blinded with rage over Mirbach’s murder.”

Some even claimed they were not defending themselves from the Bolsheviks at all, but rather from “German agents and the prisoners of war they were arming,” who allegedly filled the streets of Moscow at the time. In short, the notion of a defensive uprising became a standard trope in SR writings: the struggle, they insisted, was directed against “the policy of the Council of People’s Commissars, and by no means against the Bolsheviks themselves.”

However, even within the Left SRs there were those who clearly recognized the flaws in this logic: if the Soviet government was composed of Bolshevik leaders, it was impossible to oppose its policies without demanding their removal. Isaac Steinberg, a member of the Central Committee and the former People’s Commissar of Justice, openly proposed “to go for power.” Yet this understanding never translated into real action: most Left SRs, it seems, were not prepared to openly confront their former revolutionary comrades. “They lacked an energetic and talented commander,” Vatsetis summed up the situation. “Had they had one, neither he nor the Left SRs would have spent July 6 and the entire night of the 7th in idle hesitation.”

Most Left SRs were not ready to openly confront their former revolutionary comrades.

The Left SR uprising went down in history as just another failed rebellion. In fact, since March 1801 — when the imperial guard last deposed one tsar and installed another — Russia has seen only one truly successful coup: the Bolshevik seizure of power on November 7, 1917. All other attempts ultimately amounted to nothing more than “a show of threat.” When Lenin found himself in a situation much like the one he had created for the previous Russian government the year before, it turned out that there was no second Lenin to be found.