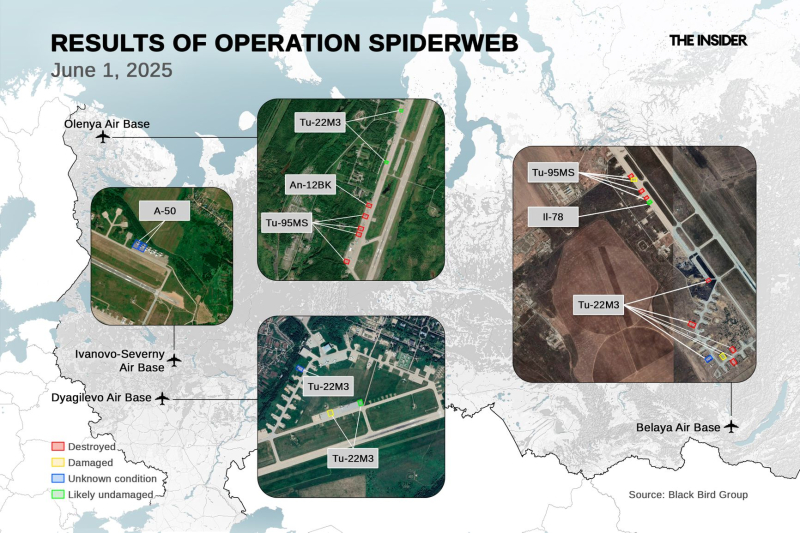

Photo: Maxar Technologies

On June 1, 2025, Ukraine’s Operation Spiderweb made headlines after FPV drones began striking Russian strategic bombers as far north as the Arctic Circle. Three months later, the full effects of the attack are becoming clearer. About 20% of Russia’s combat-ready long-range bombers were put out of action, but that’s far from the full extent of the damage Ukrainian drones inflicted. For Moscow, using bombers to launch missile strikes on Ukraine has now become far more complicated logistically — and much more expensive. Most of Russia’s remaining bombers were redeployed to bases in the country’s Far East, meaning they must fly as many as 10,000 extra kilometers on each combat mission. In the long term, that threatens to accelerate the wear and tear of aging planes. Key indicators suggest that Russia’s Aerospace Forces are already facing technical problems operating the bombers under these new conditions.

On June 1, 2025, more than 100 Ukrainian first-person view (FPV) drones hidden inside containers on the backs of trucks emerged almost simultaneously to attack airfields inside Russia:

- Olenya in the Murmansk Region in the Arctic

- Dyagilevo in the Ryazan Region in central Russia

- Belaya in Siberia’s Irkutsk Region

- Ivanovo-Severny in the Ivanovo Region in central Russia

The Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) spent around a year and a half preparing the operation, dubbed “Pavutyna,” Ukrainian for “Spiderweb.” It produced a massive media impact: footage of drones costing less than $1,000 each delivered explosives into the sides of multi-million dollar long-range aircraft, which were protected by little more than the car tires laid across their fuselages. Analysts (1, 2) characterized it as a fundamentally new stage in the practice of asymmetric warfare.

Three of the four airfields that were struck housed Tu-95MS strategic bombers, Tu-22M3 long-range missile carriers, and Tu-160 strategic bombers. All belong to the air component of Russia’s nuclear triad, as they are capable of carrying nuclear warheads. Another target, the Ivanovo-Severny (lit. “Ivanovo-North”) airfield, hosted military transport aircraft and early warning and control planes.

The only base not reached was Ukrainka in the Amur Region, which borders northeast China. The truck carrying drones to the area caught fire and exploded en route.

The SBU put the losses at 41 aircraft, with total damage totaling around $7 billion. The agency released a detailed video showing the drone strikes on the four Russian airfields. According to analysis by the Ukrainian open source intelligence (OSINT) project DeepState, the footage depicts attacks on 25 aircraft. Another Ukrainian OSINT team, CyberBoroshno (lit. “CyberFlour”), calculated that 22 or 23 aircraft were hit, among them19 Tu-95MS and Tu-22M3 bombers.

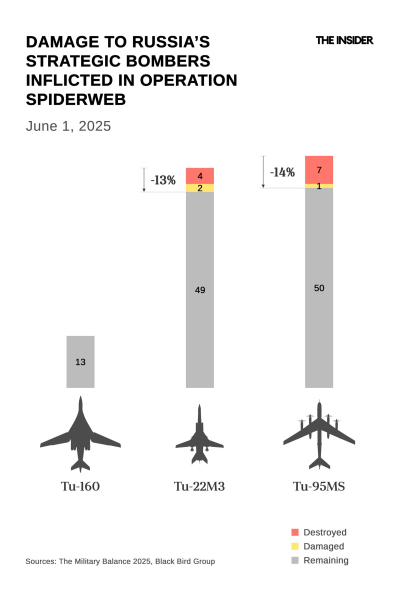

Emil Kastehelmi of the Black Bird Group said that seven Tu-95MS strategic bombers and four Tu-22M3 long-range missile carriers were definitively destroyed. Another Tu-95MS and up to seven Tu-22M3s were damaged, though some may not have been flight-worthy to begin with.

Overall, the most credible assessment is that 12 to 14 Russian strategic bombers were knocked out of service, at least temporarily. That represents up to 15% of the total known fleet of such aircraft.

Most of the drones appear to have struck operational planes, meaning about 20% of Russia’s combat-ready Tu-95MS and Tu-22M3s were actually lost. There is no confirmed evidence from available footage that Tu-160s were hit.

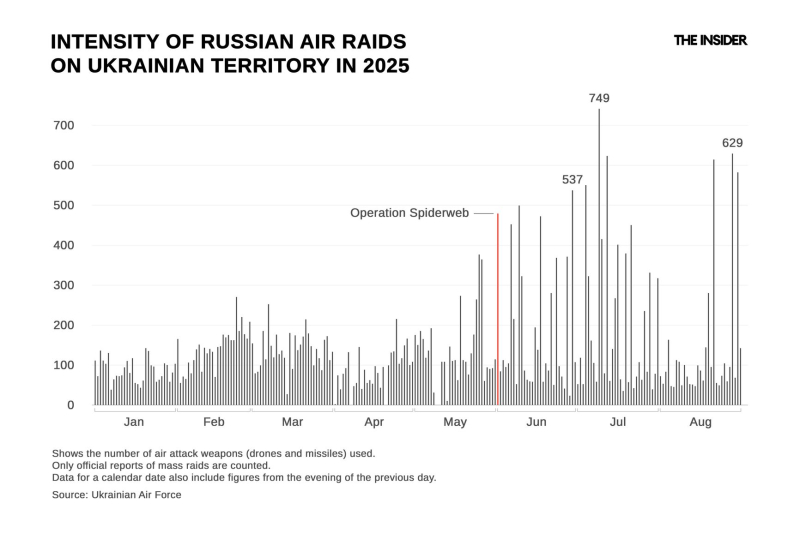

Despite the damage, Russian air raids on Ukraine only intensified after Operation Spiderweb. Over the course of 2025, the number of aerial weapons used in strikes rose from an average of about 90 a day in January to 140 a day in August. The heaviest strikes of the war, with more than 500 missiles and drones launched, have all occurred since June 1, 2025. In other words, the blow to Russia’s strategic aviation did not reduce the pressure on Ukraine’s air defenses.

The ratio of drones to missiles in Russian attacks has remained largely unchanged: drones account for 95-97%, with missiles making up the rest. But missiles carry far greater combat value for two key reasons: they are more difficult to intercept, and they carry much larger warheads than Shahed-type drones.

Russia employs land-, sea- and air-launched missiles against targets beyond the tactical depth of the front. In practice, only a small set of systems are used with any regularity: the Iskander-M and Iskander-K from Iskander launchers, Kalibr sea-launched missiles, and the Kh-101, Kh-55 and Kh-555 air-launched missiles, along with the Kinzhal and Kh-59/Kh-69.

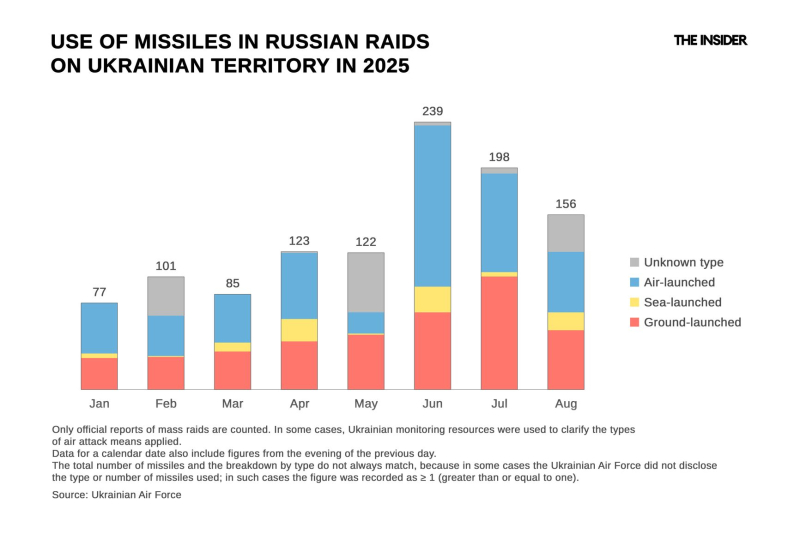

Tu-95MS and Tu-160 strategic bombers launch Kh-101 cruise missiles (and similar Kh-55 and Kh-555), which carry 400-kilogram warheads. The Tu-22M3s that were hit in Operation Spiderweb are designed to launch Kh-22 and Kh-32 missiles, originally intended for strikes on carrier groups, with warheads weighing nearly a ton. For reasons unknown, only isolated launches of Kh-22s have been recorded since February 2025. Both the Kh-101 and Kh-22 exist in nuclear variants, which is why their carriers are classified as strategic aviation.

Since June 1, Russia has increased both its overall missile use in strikes on Ukraine and its reliance on air-launched weapons. The main growth has been in Kh-101s and Kinzhals (though the MiG-31Ks that carry Kinzhals do not formally qualify as strategic aviation). At the same time, the role of strategic bombers in the campaign has shifted fundamentally, with potentially far-reaching consequences for the combat readiness of Russia’s Tu-95MS and Tu-160 fleet.

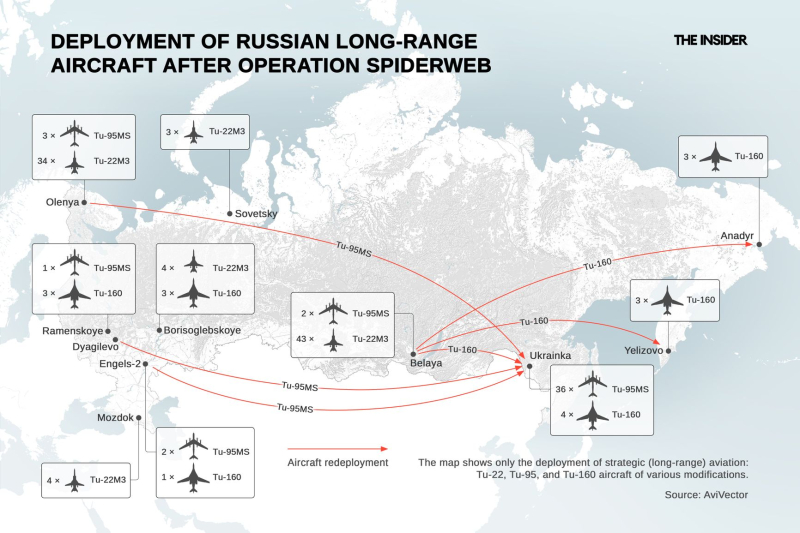

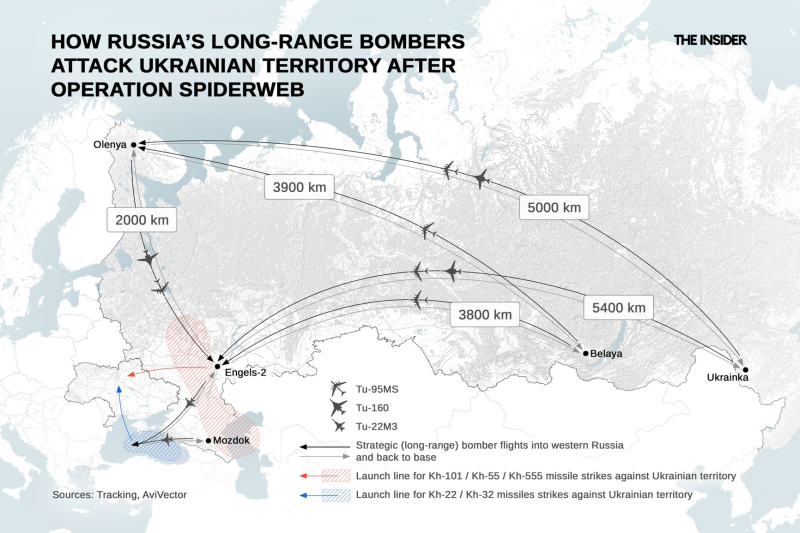

To prevent further attacks like Operation Spiderweb, Russian commanders have redeployed many Tu-95MS and Tu-160 bombers to the Far East, mainly to the Ukrainka air base in the Amur Region — located around 8,000 kilometers from the war zone. Even aircraft previously kept at the Olenya in Murmansk Region — nearly 2,000 kilometers from Ukraine — have made the move. Tu-160s from Belaya air base were dispersed even farther away: to Anadyr in Chukotka (which borders the U.S. state of Alaska) and Yelizovo in Kamchatka.

Since June 2025, Ukrainka has been used regularly for combat missions and now serves as the main base for Tu-95MS bombers. The problem is that this redeployment has not been accompanied with changes in logistics or command procedures. Aircraft are still serviced, armed, trained, and refueled at Engels-2 (near Saratov) and Olenya before returning to the Far East (1, 2).

Ukrainka airfield, located over 8,000 kilometers from the frontline in Ukraine, now serves as the main base for Tu-95MS bombers.

The launch areas for strikes on Ukraine have not changed. Kh-101 and Kh-55 missiles are typically fired from airspace over Russia’s Saratov, Volgograd, and Astrakhan regions, or from over the Caspian Sea. The less frequently used Kh-22 and Kh-32 are launched from over the Black Sea. That means sorties by Tu-95MS and Tu-160 missile carriers now require far more time and resources for flights, intermediate landings, and launches. Ukrainian monitoring groups have recorded at least one attempt to carry out strikes by flying directly from Far Eastern bases such as Belaya, but such missions require aerial refueling by multiple tanker aircraft and place excessive strain on crews.

A standard Tu-95MS sortie from Ukrainka now covers more than 12,000 kilometers and involves 23 hours of flight time.

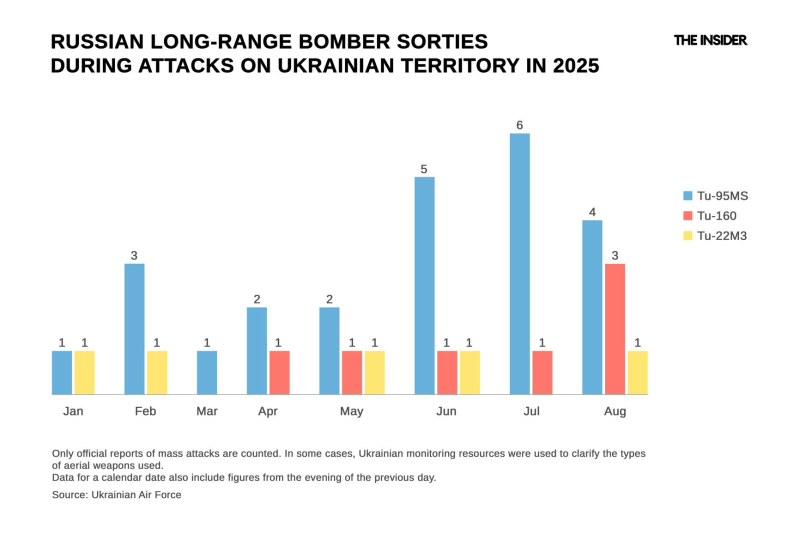

However, the dramatic increase in strain on both aircraft and crews has come alongside a paradoxical rise in sortie frequency. Data from Ukraine’s Air Force and independent monitoring projects indicate that Tu-95MS bombers, along with Russia’s handful of operational Tu-160s, are flying combat missions far more often than before Operation Spiderweb — back when they did not have to log an additional 10,000 kilometers from Russia’s Far East.

Operating the Tu-95MS and Tu-160 under these conditions is clearly accelerating wear and tear while also significantly raising the cost of missile strikes for Russia. Neither type of aircraft has been manufactured since the early 1990s, and today’s limited Tu-160 production relies on Soviet-era stock. For example, NK-12MP engines on the Tu-95MS reportedly have a lifetime of 5,000 flight hours, with no more than 200 hours annually for each plane. At 23 hours per combat mission — compared with 4–5 hours before Operation Spiderweb — that annual limit could be exhausted in just eight or nine sorties. The cost for an overhaul of a Tu-95MS is estimated at $50 million.

The exact cost per flight hour for Tu-95MS and Tu-160s is unknown, but estimates from the late 2000s put Tu-160 operating costs at more than $20,000 per hour, not including missile use. Even if that figure has not risen, expenses have jumped from $80,000-$100,000 per sortie to nearly $500,000.

There are signs that Russia’s new system of organizing bomber strikes on Ukraine is already causing technical problems. The well-known insider channel Dossier Shpiona (lit. “A Spy’s Dossier”) claimed that during a raid on Sept. 3, one Tu-160 failed to launch its missiles due to a malfunction in its firing mechanism, while another was unable to take off from the Engels-2 air base.