Vladimir Putin and Governor of the Bank of Russia Elvira Nabiullina

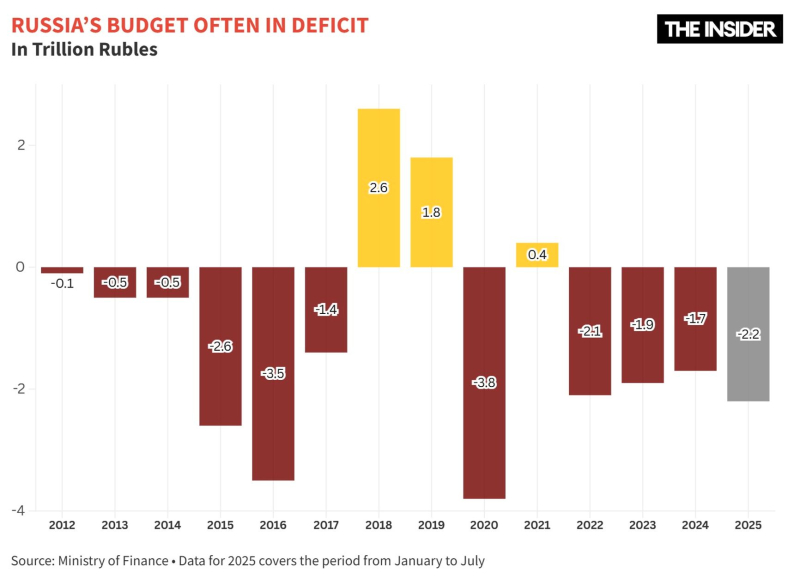

Before his trip to Alaska, Vladimir Putin boasted of Russia’s stable federal budget and record-low inflation and unemployment rates. Unsurprisingly, none of what Putin said happens to be true. First, the federal budget is in an unusual predicament. Second, even official data forecasts anemic economic growth — if not a looming depression. This does not mean that, once its reserves are depleted, the Kremlin will automatically have to stop the war. Instead, if oil prices remain unchanged and reserves do indeed run dry within a year, Putin may yet resort to what he has avoided doing throughout his rule: turning on the printing press and building a debt pyramid.

Monetary values in this article are given in rubles only, as the focus is on relative changes in the Russian economy rather than on the absolute dollar value of those changes. For the sake of reference 1 trillion rubles is roughly equal to $12.3 billion.

Only time can tell how critical Russia’s economic situation is at the moment, but by all indications, time is running out for its current model. At an Aug. 12 meeting on economic issues, Putin highlighted a 14% increase in non-oil-and-gas revenues but failed to mention that overall revenues in the same period rose by only 2.8%, while expenditures grew by 21%. The federal budget deficit for the first seven months of 2025 is already 4.5 times greater than it was in 2024, standing at 4.9 trillion rubles — already higher than the record annual deficit of 4.1 trillion that was set in the pandemic year of 2020.

The Ministry of Finance explained that this year's expenditures have been distributed more evenly than usual, suggesting that the current pace of deficit spending may be an anomaly:

“This is mainly due to the front-loaded financing of expenditures in January of this year, as well as a decline in oil and gas revenues; however, it will not affect the achievement of the target structural balance parameters for 2025 as a whole.”

How exactly can the authorities meet their targets despite the seemingly precarious current situation?

To generate the planned amount of revenue, the treasury’s monthly income would need to surge by 24% from the current average of 2.9 trillion rubles per month collected in January–July. At the same time, expenditures would need to be reduced by 5%, to 3.42 trillion rubles. Such a shift has never been achieved before. In 2024, for example, the federal budget’s average monthly revenues from August to December were indeed 20% higher than in January–July, but expenditures were 30% higher.

An economic isolation policy aimed at achieving self-sufficiency and independence of the national economy from external ties, with the goal of meeting all needs through domestic resources and production.

The difference between the government’s funds in accounts at the central bank (the government’s claims on the CBR) and the amount the government owes the central bank (government bonds on the CBR’s balance sheet).

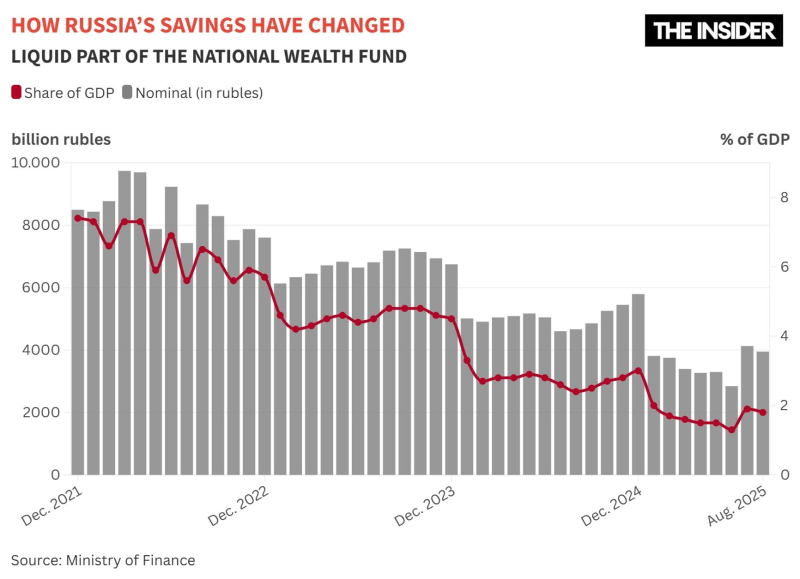

The liquid part of the NWF consists of assets not invested in stocks or bonds, held in accounts at the Bank of Russia in rubles, yuan, and gold. As of August 1, it amounted to 3.95 trillion rubles, or 1.8% of GDP.

In 2024, from January to July, it was about 1.2 trillion, while in the same period of 2025 it had already reached 1.7 trillion.

Even if it were possible to repeat the more favorable trajectory of 2023, by the end of 2025 revenues would reach 40.7 trillion rubles, expenditures 46.6 trillion, and the deficit would still be a whopping 6.9 trillion. But such a turn is unlikely: this year, even May and June, which had traditionally ended with a surplus, ran a deficit. In short, a “2024 scenario” is more probable than a “2023” one, meaning the deficit could reach upwards of 10.7 trillion rubles, or 5% of GDP.

In relative terms, this would be Russia's worst deficit since 2009 (when it was 5.8% of GDP) and would be comparable to the U.S. deficit (6.5% of GDP). Up until now, Russia had managed to maintain a healthier budget than most G7 countries.

An economic isolation policy aimed at achieving self-sufficiency and independence of the national economy from external ties, with the goal of meeting all needs through domestic resources and production.

The difference between the government’s funds in accounts at the central bank (the government’s claims on the CBR) and the amount the government owes the central bank (government bonds on the CBR’s balance sheet).

The liquid part of the NWF consists of assets not invested in stocks or bonds, held in accounts at the Bank of Russia in rubles, yuan, and gold. As of August 1, it amounted to 3.95 trillion rubles, or 1.8% of GDP.

In 2024, from January to July, it was about 1.2 trillion, while in the same period of 2025 it had already reached 1.7 trillion.

Relative to GDP, Russia's 2025 deficit could be the largest since 2009

The federal budget deficit poses a particular problem for the Russian authorities, as financing it under current conditions presents a serious challenge. Currently, two options are available: domestic borrowing, and spending from reserve accounts. However, with interest rates rising and reserve accounts shrinking, neither option is attractive. The liquid portion of the National Wealth Fund (NWF) is already dipping below 4 trillion rubles, and in the absence of fundamental changes, this amount will last an estimated four months at best.

An economic isolation policy aimed at achieving self-sufficiency and independence of the national economy from external ties, with the goal of meeting all needs through domestic resources and production.

The difference between the government’s funds in accounts at the central bank (the government’s claims on the CBR) and the amount the government owes the central bank (government bonds on the CBR’s balance sheet).

The liquid part of the NWF consists of assets not invested in stocks or bonds, held in accounts at the Bank of Russia in rubles, yuan, and gold. As of August 1, it amounted to 3.95 trillion rubles, or 1.8% of GDP.

In 2024, from January to July, it was about 1.2 trillion, while in the same period of 2025 it had already reached 1.7 trillion.

The government’s net claims on the Central Bank account for another 5.1 trillion rubles, which would last roughly seven months. Overall, the Kremlin has enough reserves to fund the budget until August 2026. If nothing changes, it will then have to either borrow approximately 1 trillion rubles each month or generate this amount by printing money. In any case, Russia would find itself in a completely new — or rather, long-forgotten — macroeconomic reality, one that Putin has tried to avoid for 25 years.

The heaviest burden on the Russian budget is, of course, military spending, with the federal center alone planning to spend 13.2 trillion rubles in 2025. This amount can be divided into peacetime expenditures and purely military costs. In prewar 2021, Russia's federal defense spending amounted to 2.7% of GDP, which corresponds to 6 trillion rubles in 2025. The remaining 7.2 trillion rubles can be attributed directly to the war in Ukraine.

In addition to the federal budget, the war is being funded by regional governments and state-owned companies. Last year, 813 billion rubles were allocated in regional budgets for war-related purposes, and over the past year this amount grew by almost 50%. If growth continues at this rate, in 2025 the regions will spend roughly 1.2 trillion rubles on military needs, of which only 300–400 billion can be attributed to the kinds of standard defense expenditures seen during peacetime. Most of the regions’ military budgets cover allowances for servicemen and their families, support for refugees, and compensation for civilian casualties. Regions also spend a significant amount on civil defense, which includes outlays for bomb shelters and firefighting.

An economic isolation policy aimed at achieving self-sufficiency and independence of the national economy from external ties, with the goal of meeting all needs through domestic resources and production.

The difference between the government’s funds in accounts at the central bank (the government’s claims on the CBR) and the amount the government owes the central bank (government bonds on the CBR’s balance sheet).

The liquid part of the NWF consists of assets not invested in stocks or bonds, held in accounts at the Bank of Russia in rubles, yuan, and gold. As of August 1, it amounted to 3.95 trillion rubles, or 1.8% of GDP.

In 2024, from January to July, it was about 1.2 trillion, while in the same period of 2025 it had already reached 1.7 trillion.

In 2025, Russia's regions will spend roughly 1.2 trillion rubles on military needs, of which only 300–400 billion can be attributed to standard defense expenditures

In aggregate, federal and regional war expenditures total approximately 8 trillion rubles per year. Some estimates are even higher: according to Dr. Janis Kluge, a research fellow at the German Institute for International Security Affairs, the cost reached 47 billion rubles per day in the first half of 2025, a figure that would mean over 17 trillion rubles in annual spending if it proves to be representative.

Even calculating based on official statistics, if Russia were to revert to levels of peacetime military spending, the savings of roughly 8 trillion rubles per year still might not be enough to eliminate the federal deficit. In the first seven months of 2025, the deficit averaged nearly 700 billion rubles per month, while the war is costing around 660–670 billion.

An economic isolation policy aimed at achieving self-sufficiency and independence of the national economy from external ties, with the goal of meeting all needs through domestic resources and production.

The difference between the government’s funds in accounts at the central bank (the government’s claims on the CBR) and the amount the government owes the central bank (government bonds on the CBR’s balance sheet).

The liquid part of the NWF consists of assets not invested in stocks or bonds, held in accounts at the Bank of Russia in rubles, yuan, and gold. As of August 1, it amounted to 3.95 trillion rubles, or 1.8% of GDP.

In 2024, from January to July, it was about 1.2 trillion, while in the same period of 2025 it had already reached 1.7 trillion.

Even if the war ends, the savings may still be insufficient to eliminate the federal deficit

The fiscal crisis has arisen not only due to bloated wartime expenditures, but also because of insufficient tax revenues.

Russia's economy is expected to grow by 2.5% over the year, according to the Ministry of Economic Development’s baseline scenario, though a more pessimistic scenario predicts growth of about 1.8%. So far, however, growth rates have been even lower: 1.4% in the first quarter and only 1.1% in the second. The Minister of Economic Development, meanwhile, expects growth to stop entirely and warns that there is real risk of a recession.

An economic isolation policy aimed at achieving self-sufficiency and independence of the national economy from external ties, with the goal of meeting all needs through domestic resources and production.

The difference between the government’s funds in accounts at the central bank (the government’s claims on the CBR) and the amount the government owes the central bank (government bonds on the CBR’s balance sheet).

The liquid part of the NWF consists of assets not invested in stocks or bonds, held in accounts at the Bank of Russia in rubles, yuan, and gold. As of August 1, it amounted to 3.95 trillion rubles, or 1.8% of GDP.

In 2024, from January to July, it was about 1.2 trillion, while in the same period of 2025 it had already reached 1.7 trillion.

Civilian sectors are already declining. The government-affiliated Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-Term Forecasting (TsMAKP), headed by Defense Minister Dmitry Belousov’s brother, notes that civilian production has been shrinking by 0.8% per month since the beginning of the year. “Autarky is not working,” the TsMAKP report states, dismissing hopes for a sufficiently large domestic market in Russia as illusory.

Economists believe the economy will plunge into a prolonged recession in October 2025: “The contraction in the physical volume of GDP (over a rolling year) could continue for more than four consecutive quarters.” Even the pro-government Institute of National Economic Forecasting of the Russian Academy of Sciences admits the decline has already begun: Russia's GDP appears to grow only when compared to the same quarters of the previous year, but declines compared to the last quarter of 2024.

An economic isolation policy aimed at achieving self-sufficiency and independence of the national economy from external ties, with the goal of meeting all needs through domestic resources and production.

The difference between the government’s funds in accounts at the central bank (the government’s claims on the CBR) and the amount the government owes the central bank (government bonds on the CBR’s balance sheet).

The liquid part of the NWF consists of assets not invested in stocks or bonds, held in accounts at the Bank of Russia in rubles, yuan, and gold. As of August 1, it amounted to 3.95 trillion rubles, or 1.8% of GDP.

In 2024, from January to July, it was about 1.2 trillion, while in the same period of 2025 it had already reached 1.7 trillion.

Economists expect Russia’s economy to enter a prolonged recession in October

At the very least, the civilian sector of the economy is shrinking. Meanwhile, as Putin noted, tax revenues from it are rising due to higher levies — but they are rising very slowly and still lag far behind the growth of expenditures.

The process could be compared to excessive milking of a shrinking cow. The practice of milking more while feeding less has never benefited either farming or the economy.

The manufacturing sector in particular will continue to deteriorate, and to maintain even previous levels of tax revenue, the government will have to further increase its relative tax burden. In turn, this will continue to shrink the taxable base, creating a vicious cycle. The only way out of this spiral would be through large external inflows or strict austerity.

There is no reason to believe that Russia's military sector will face cuts, even if the government is forced to reduce spending elsewhere. On the contrary, it may even be expanded at the same time other sectors are experiencing a regime of increased austerity.

The process has already begun, with Russia cutting its social spending from 9 to 6.5 trillion rubles in this year’s budget. Another such cut would earn the Kremlin enough funds for an additional two to three months of war.

Half a trillion rubles have already been saved in the “National Economy” category: 4.35 trillion compared to 4.85 trillion in 2024. Spending on the national economy mainly consists of subsidies and government investments; from a liberal-market perspective, these could safely be cut to zero.

While this move would be completely out of character for the current regime, it would provide an additional four to five months of war funding. For the population, the measure would be a short-term shock: many industries would cease to exist, and the prices of a range of goods and services would rise sharply, even if the market would eventually adapt.

Another potential source of savings is the currently untapped housing and utilities sector, where federal spending has increased from 1.15 trillion rubles in 2024 to 1.8 trillion in 2025. With a reduction to 1.44 trillion planned for 2026, it would make financial sense to implement this cut immediately rather than wait until the calendar changes. However, such a step would be certain to trigger social tension and accelerate the ongoing decline in the state-dependent construction sector — and the payoff would only be worth a couple months of relief. The regime could also save around 500 billion rubles per year on environmental protection, where spending in 2025 has nearly doubled (from 480 to 914 billion). Given that, in the Kremlin’s estimation, human lives are disposable, there is no reason to suspect that the natural environment is a priority.

At this point, the potential for cutting expenditures has been largely exhausted. Education and healthcare are already being economized, while “security and law enforcement” are untouchable. Obligatory debt service payments will only increase, and the remaining minor items cannot make much of a difference.

From a financial perspective, war is always a catastrophe. A convergence of circumstances allowed Russia to gloss over this truth for three years. Now, however, everyone will have to acknowledge the elephant in the room: it was the war that put the 2025 federal budget into a truly catastrophic state.

The government’s domestic debt is snowballing, while financial reserves — especially claims on the Central Bank — are rapidly depleting. If these are reduced to zero, and if the liquid portion of the NWF is used up, current expenditures could be maintained for roughly one more year before a crisis arrives.

If Russia were to take a hatchet to spending on the economy, social policy, and housing and utilities, it could go on for an additional nine or so months — at the cost of momentous structural shifts nationwide. Naturally, the voices of reason within the state bureaucracy advocate for less drastic approaches. They favor seizing the opportunity to conduct real peace negotiations. Whether or not their calls are heeded by the Kremlin is an entirely separate matter.

An economic isolation policy aimed at achieving self-sufficiency and independence of the national economy from external ties, with the goal of meeting all needs through domestic resources and production.

The difference between the government’s funds in accounts at the central bank (the government’s claims on the CBR) and the amount the government owes the central bank (government bonds on the CBR’s balance sheet).

The liquid part of the NWF consists of assets not invested in stocks or bonds, held in accounts at the Bank of Russia in rubles, yuan, and gold. As of August 1, it amounted to 3.95 trillion rubles, or 1.8% of GDP.

In 2024, from January to July, it was about 1.2 trillion, while in the same period of 2025 it had already reached 1.7 trillion.